I had the wonderful opportunity to interview Elson Bankoff, who is currently a senior at Sidwell Friends School and will be attending Harvard College next year. She is the founder and Editor in Chief of the Ecosystemic Magazine, a youth-run environmental action journal. She also organizes climate strikes for Fridays For Future and produced a play called If The Bells Would Ring. We discussed her extraordinary accomplishments, journey, and experience navigating the arts and activism.

Part 1: The Beginning

Hello, Elson! Thank you for joining us for an Earth Chronicles Interview. Can you tell us about yourself? (Where are you from or current positions)

I am from Washington D.C., which is a great place to grow up because it inherently makes you interested in policy and activism or even local and national events because you are in this hub. But also, a lot is going on with the city itself because there is a lot of culture and great things happening all the time. So, it’s great that I have been exposed to that.

I am a senior at Sidwell Friends School, and I will be attending Harvard University next year, which I am very excited about. I am the founder and Editor in Chief of the Ecosystemic Magazine, which is a youth-run environmental action journal, I’d say. I’ve organized with Fridays for Future for strikes and also produced a play called If The Bells Would Ring this year.

How did you start or become interested in climate activism?

I like policy. I love doing creative things and exploring different mediums, and being sort of a social entrepreneur in a way. I definitely do not restrict myself to advocacy because it’s great to be an activist and to always be fighting for a cause. But I think, especially with climate stuff, we are nearing a time when we can actually start to invent the solutions themselves instead of just asking for them. So I think a lot of my activism has been around that. So that’s kind of how I became interested in it. First of all, I was terrified of the threats and very thankful for my education because I think education plays an important role in the involvement of this movement because there are a lot of scientific and political connotations with it. So, I was really fortunate to learn a lot about it in middle school and learn about intersectionality a lot. I was able to take passions that I have, aside from climate resilience, and intertwine them with fighting for the cause. I was really into the STEM aspect of it for a while (like hydrogen and renewable energy), and I am coming back to that right now. But it was a very inventive side. And then, I sort of shifted to being like, Wow, a lot of this exists, but it’s so frustrating that none of it’s put into play. So, I got really into the policy and the actual advocacy because I realized it’s really hard to get involved in policy when you’re not in office. So that’s what advocacy is! And also the arts and writing and the play If The Bells Would Ring.

How do you balance your climate activism work with other activities?

The way to sustain your activism is to sort of not see it as something detached from things you enjoy doing. You should take the things you enjoy doing and connect them back to a greater cause. I’ve learned I’ve been able to learn all these random skills, even down to things like video editing, that I wouldn’t entirely attribute to climate activism. But I would really just mess around and create trailers for our club to promote our environmental club at school. I got really into video editing, I started doing it for a bunch of other projects, and I ended up doing this whole Covid documentation project. And sometimes, when you do something for a cause, you end up enjoying it in so many different contexts. So, I think if anything, if you are really moved by climate activism like I was, or not even moved or just frightened or felt that you had a purpose in a sense or felt like you had to do something, I think you end up picking up all these random skills. Like I fully know so much about the off-broadway theater community. I can fully navigate that. And I now know about directing, writing, and the whole process of producing a play that I never thought I would care about. And I wouldn’t have even thought that was a passion of mine. But now, I have this whole new skill set just because I had this vision for a climate advocacy piece. I think the activities, the things I am interested in, stem from this initial caring about something. And a lot of the time, it’s about climate change and finding a way to do something about it.

Also, though, obviously, there’s a social component, like I have so many great friends who are awesome. I spend a lot of time with them; I’m a very extroverted and social person. And it’s great because a lot of my friends also care about the same stuff, But I also think it’s important not to root your friendships in certain things because sometimes it’s nice to have something you’re working really hard on and for them to support you but not necessarily doing everything with you because they might have different interests. But you can also encourage them to tie their interests into other things. Like my friend who’s interested in finance and business, we have so many great conversations about the investment implications of a renewable economy. And it’s really cool to merge interests; I don’t think it has to be separate, but it doesn’t have to be like the foundation of your friendships.

Part 2: Organizer at Fridays for Future, D.C.

You are the Lead D.C. Area high schools organizer for FFF in D.C., mobilizing students in your city for climate strikes. What does it take to organize a global climate strike? What is the process like? Are there any challenges? Or things you’ve learned?

For organizing a strike, the main one I did was last March which was the first big global climate strike after Covid since 2019 when there was the Greta one, which was very big.

Organizing strikes is very beneficial to your local community if you really want to meet people and create a scene wherever you’re from. It’s really beneficial. I do not think it’s necessarily the main thing that’s going to cause—if you actually want to actually change policy, there is stuff you can do. But it’s a great starting point. If you really don’t know anyone in your area who does climate activism, this is a great way to get people to care because it’s very simple and it’s very like, “Oh hey, you’re going to miss school and go out on the street with a sign,” and that’s how you get people involved in the initial state.

Like the question about how I got involved, a lot of it was just a bunch of seniors when I was a freshman just being like, Hey, there’s a climate strike, come by, and then you sort of are just exposed to this huge world of really passionate people. And it’s hard, I think, at a young age, especially when there’s so much happening in this world with so much stimulation, like you have all these things on your phone and everything, like it’s hard to find something that you really wholly care about and are passionate about. So that’s why exposure is great.

So basically, what it takes, you have to find pinpoints in different schools. I was in charge of mobilizing highschoolers in the D.C. area, so I basically had to reach out to random people who may have used to go to my school, or I knew them from like a sport or some random stuff, so I was like hey can you connect me with your environmental club leader or if they didn’t have one I would find someone else, so basically I got these contacts from all these different schools, and they became leads.

So I think it’s really important to value each specific person and not have an ego about it. There should not be a hierarchy with strike organizing. It’s important for there to be leadership, but I think every single person should really be valued. So basically, what we did was, “So you’re now a school leader, so you are in charge of your school,” so that’s a leadership position for them. And if they’re doing it for college, they’re doing it for college, but that doesn’t fully matter because they’re now fully invested, and they eventually might start a club at their school or keep getting really into it. And that was the case; I ended up getting service hours which typically wouldn’t happen, but the reason why was there was a spike in environmental advocacy clubs in the area after the strike, which was really cool. So basically, find the context, then they’ll mobilize all these people, and then you have a ton of people to show up. We had like 600 people for the march strike.

Part 3: Ecosystemic Magazine

The Ecosystemic Magazine is an incredible collection of outstanding work and thought-provoking reads. What inspired you to start?

Ecosystemic Magazine started as a newsletter for an environmental club, FEAT, that has existed for a long time, but I currently run it. A junior started it for his senior project, it was just a newsletter, and we got some writers. And then I joined this thing called SEASN, student environmental and sustainability network, which was initially a group of Quaker schools, but we have extended past that where we kind of just discuss things like sustainable solutions. It kind of became Ecosystemic because we just introduced the newsletter to a broader network, and people started writing. And we realized that a lot of our goals as a network for SEASN could happen through the magazine, and it was a very easy thing to pitch to people. So we basically got all these schools in the network, and we got more than fifty schools. We’d have people who’d be contact points for schools in all the countries, and they’d get people to write from their schools. We would publish it, send it out, and built the website. And then people start writing things like Oh, this is how I mobilized people for my strike or This is our proposal to bring composting to our school. You can just publish that stuff which is what we wanted to do with our network initially, but it just happened to work really well in a magazine form, so it was one of those things that just evolved. No one just went out and was like, I’m going to found a magazine. And, I think that it’s important to just let it evolve. Especially with ambitious projects, it can be a lot to be set in stone. So, let it be creative and let it evolve.

Are you the one who draws the cartoons? If so, could you tell us more about them?

Yes, I am the one who draws this cartoon. Back to the thing about random skills, I fully did not expect to be a cartoonist. It’s actually so fun. I actually put this skill on my random skill on the end-of-the-year poll on my story. And I’m a big fan of the New Yorker and definitely took a lot of inspiration from their website for this because I think people want that kind of artistic and aesthetics. It’s important to intertwine pop culture into advocacy. Especially environmental advocacy because you can’t really see it as separate. It has to be cool and fun, so I like cartoons. It started out as a way to get a graphic for cover art for each of the publications and make the site look nice. But I love it, and I do it every single time.

Why do you think it’s important to publish student work about climate activism and social change through creative expression?

I think it’s essential to publish student work about climate activism and social change through creative expression because I think people have a lot to say, and it’s really difficult to have a place to say that. There’s not necessarily a class that’s just on this. You don’t have a place to write an essay about all these complicated topics. Also, I think it’s good to slow down. With writing and art, people can really try to understand something fully.

Obviously, we’re not getting hundreds of thousands of readers. However, I think it’s more about the actual person and their journey as a writer or artist in making something that they feel like it is very whole, very practical, very practical, very creative, very them; it’s their own opinions and own analysis of something. They’re really putting their time into understanding a concept. It’s such an important niche as well.

And it’s really easy for there to be misinformation and for people to not understand things and not be thorough. A lot of the time, it’s just all happening on social media, where everything is so quick and very digestible, but you’re not fully forming a connection with the content. And when you work on something, you get this clarity and a sense of purpose and sense of, Oh, I understand this more than other people and really care about it. It makes you feel like it’s a part of you after you write a piece, and I think that’s a really cool feeling to have.

Part 4: If The Bells Would Ring

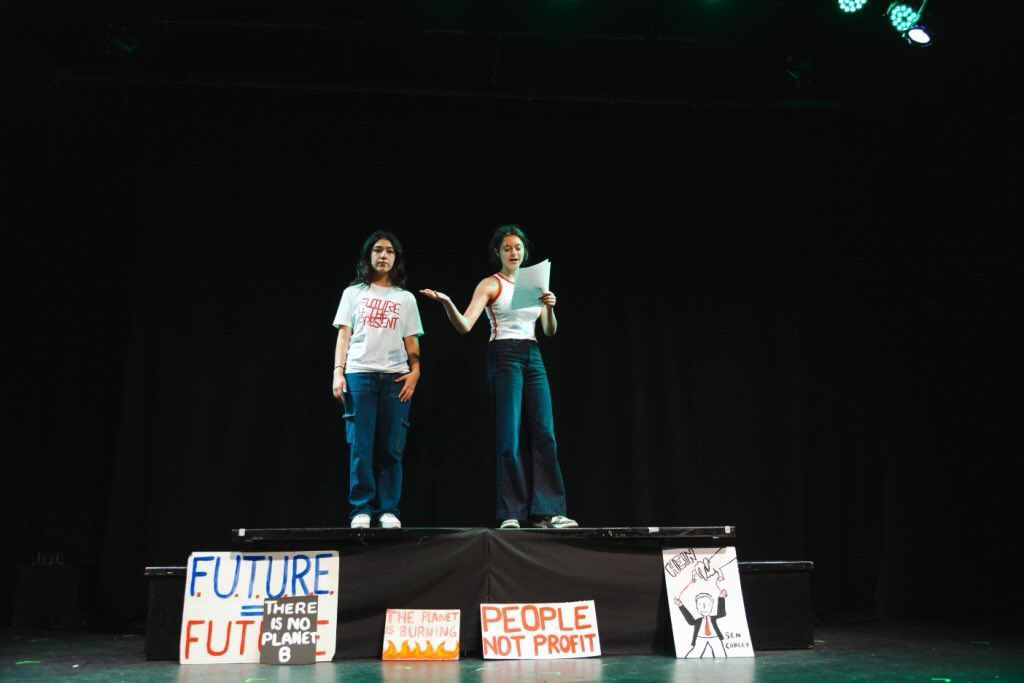

If The Bells Would Ring is a two-act political drama highlighting the passion, resilience, greed, devastation, and causes underlying the climate crisis. The play addresses influence, passivity, collective passion and political corruption. It follows the relentless modern-day climate movement and traces power from a handshake to a hurricane.

What inspired you to write If The Bells Would Ring?

I had a whole little phase with screenwriting. I had written one screenplay, and I really wanted to write another one. I was at this film-making program over the summer, and I just had—it was one of those examples where the name just pops into your head because I was like, oh, what if the bells didn’t ring and we didn’t know where to go, and we were just drifting around, and we were so subject to control and everything. But also, bells like alarms, and you know it’s good to have direction and stuff. I thought of all these metaphors, and then I was like just kind of getting into climate advocacy. This was in 2019. This was a lingering idea, and I was so upset at that point, transitioning from this sense of innovating and finding a solution myself to really being like, okay, I need to get the word out.

So in that transition, I thought of this whole plot of how upset I was about passivity and how really no one was doing enough and how it was so unsettling that we have this catastrophic and defining issue that people were literally acting like it’s a political issue that’s partisan or you can just avoid and put off. That upset me so much. So that’s what inspired me to write it. I just wanted an alarm to sound. So, I think that art, writing, and theater is a great ways to do it. I did write it as a movie at first, but I think I have to see into the character’s heads, and I think that’s best done through theater.

This production is entirely youth-written and youth-produced. What was the process like?

Not going to lie, Julianne; the process was incredibly challenging, but it was honestly beautiful to see it all happen. It was so cool. It was entirely youth-produced and youth-led. It was just connection after connection. I was reaching out to people whom I knew through different advocacy networks; they were reaching out to more people, and it was like these crazy coincidences. Like I was on this UN call, and I got a contact. Sophie Campbell was helping with the New York City Ecosystem branch, and she heard about the play from other people. She basically kind of became our stage manager, and it happened to be that her mom’s boyfriend is a Broadway actor, and he ended up starring in the show. And her mom is a theater lawyer, and she helped us out with all the logistics. But really, everyone was listening to us. One of our producers, too, had worked in the Sunrise movement production. Everyone was answering to us, and it was funny because there was a whole rule where you had to be 18 to go off on your own during rehearsals. And I was literally seventeen. And Sora, who was the other person working with FFF NYC, was also leading it and playing the lead role. We had cast everyone, and we were like spearheading the entire thing. And she was sixteen. And we literally had to have an actor supervising us for a while, and we obviously changed that role because it was sort of silly. But it was just funny because we were all just kids learning so many different things. And I think that’s why it worked, well, not entirely the reason why, but kind of why it worked whenever there was an issue or whenever some people would be a little condescending to us.

But generally, it was just amazing that it happened, and we also didn’t have a budget. No parent was sponsoring the whole thing. We fully fundraised everything and applied for grants. We used The Tank, which is a great nonprofit off-off-broadway theater in New York. And because everyone was there, I stayed in a friend’s apartment for most of the summer and would go to rehearsals and direct it. And it was amazing, and it worked out really well. We’re probably going to take it for a longer show and probably not have it be youth-led this time. But we definitely want youth people in leadership because it was very grassroots and special. But we also want it to be fully produced just for the story’s sake.

How important do you think art (in all forms) is in creating social change?

Art is probably one of the most important things in creating social change. I don’t know. I think there are different levels o fit and you kind of need everything. But I don’t think you should strictly do art. I don’t think to a certain extent, I don’t think it’s the only thing—or most effective, but I do think it plays a huge role because that’s how you create a culture around something and get people to care about it. If all people are seeing are climate data statistics, no one is going to care if it’s just a bunch of old white guys saying that this is an issue. But if people start integrating into their communities and creating murals, written word, theater, dance, film, photograph, etc. And a lot of the time, that’s what people really care about. At the end of the day, the visuals and the emotions behind them make us respond, so I think that’s really important. And it’s a great way to get involved. It’s just one of those avenues where you can be interested in art and make it about something. You don’t just have to learn a million things to be involved in the movement.

Part 5: For the Future

What would you like to say to students and the younger generations?

To students and younger generations, I am a student and a younger generation. I don’t think I’m particularly gifted in a certain area; you can kind of invent that for yourself. If you work hard and you care enough, you can become good at something. I don’t know. Just find something in the area of activism that motivates you. It’s a really crazy world, and things are changing rapidly, especially in the climate world. There’s a whole economic shift; a lot is happening with infrastructure, technology, and policy. And with all these changes, I think it’s a good time to get involved in. And you can change the world inherently because there’s a lot to study and a lot to be interested in.

Thank you so much, Elson, for joining us for the interview!

If you want to learn more about the Ecosystemic Magazine or her play, see the links below! Follow her on instagram @elsonbankoff

The views and opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect nor represent the Earth Chronicles and its editorial board.