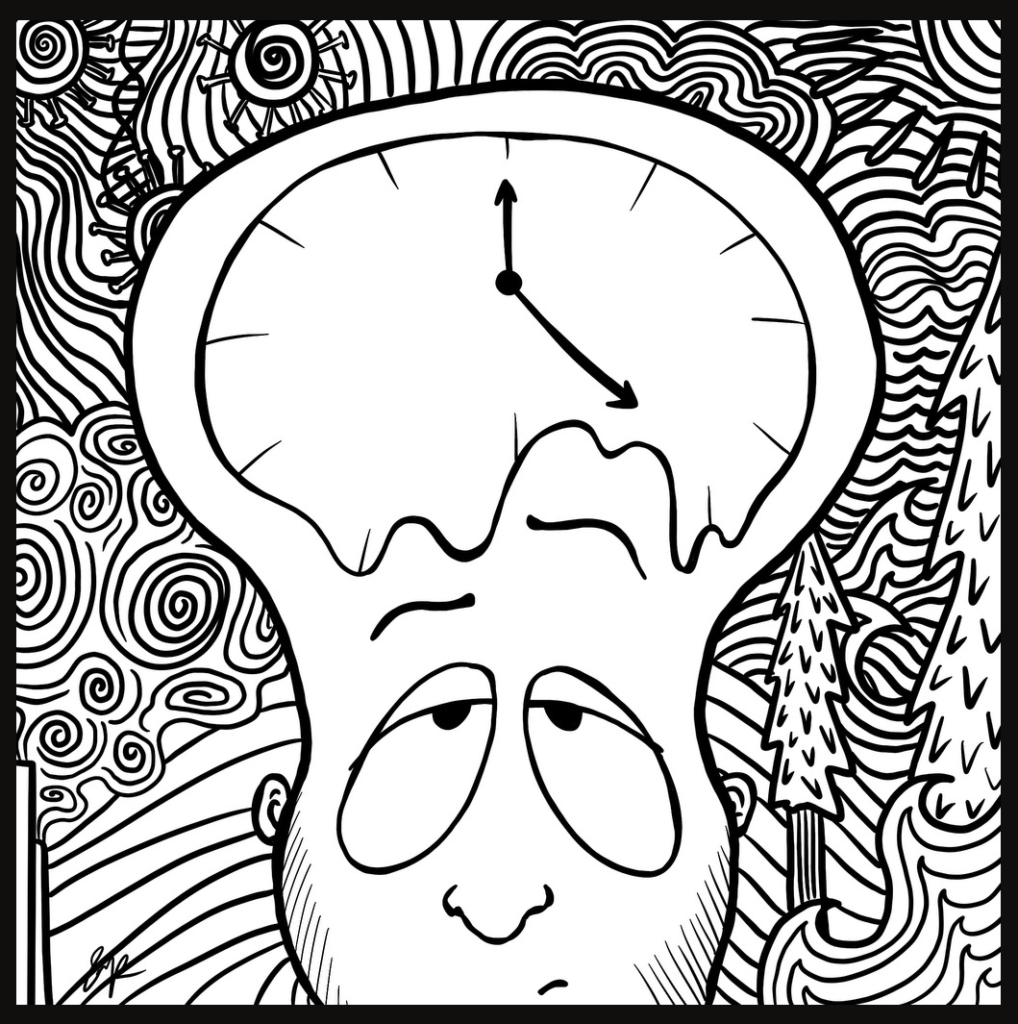

Tick tock. Seated on my gray swivel chair, I narrow my focus to the analog clock hanging opposite of my desk. Tick tock. The hands on the clock’s washed yellow screen read 3:12 p.m.; it’s been just over an hour since the school day ended. Still, a thin film of sweat covers my face from the mile-long trek home from school. It’s late October, and I’ve kept a leaf I picked up during my walk and glued into my red sticker-laden notebook. Streaks of yellow and orange paint the leaf into a mural, reflecting the familiar sunrise that peeks over the rolling foothills of the San Francisco Bay Area. Tick tock.

Most days, I only catch a listen of one or two faint clicks from the clock. The clanking of plates in the sink after dinner, muffled arguments from my mom’s work calls, and the brown noise in my headphones usually drown out the sound of the old timepiece. But here, with no distractions around me, each click sends a sound that carries a sort of sharpness throughout my home. I admire its persistence—through struggles and triumphs, childhood and adolescence, the clock has done its job, never missing a beat. But what is it counting down to?

When people discuss climate change, it’s often the same statistics: I hear about the 1.2 degrees Celsius increase in temperature, the countdown to 2050, and the millions of carbon dioxide emissions. Yet, what I don’t hear as often is why a clean, sustainable planet is worth fighting for. As thinkers, humans often resort to logical and pragmatic approaches to our issues; things like the economy, immigration, and infrastructure headline our nation’s top issues, while topics surrounding mental health and personal concerns are concealed (Pew Research Center). This disjunct between materialistic versus spiritualistic needs underscores what I believe to be the missing link that would portray climate change as one of the leading threats to our lives. It isn’t just the rising temperatures and health risks that should concern us. Instead, something much more fundamental is at risk: the foundations of our purpose to live.

The presence of nature in our lives is often overlooked, but it influences almost every single moment of our lives. This past Sunday, I hiked a trail on a nearby mountain with a group of friends. Hoping to catch the sunrise, we ran up the two-mile path, which overlooked the sprawl of suburbs stretching across the landscape. After reaching our destination, a cliff face that overlooked a stretch of canyon on the mountain, I felt not only a sense of relief but a sense of purpose. With the cool sunrise wind tickling my arm and the early calls of birds echoing throughout the canyon, I developed an appreciation of being able to experience the world around me—something I hadn’t realized I lacked as I obsessed over my daily routine of school work and studying. And while this may be a personal experience, it isn’t an isolated case. In 2024 alone, national parks were the most popular form of recreation in the United States, attracting over 325 million visitors. Consciously or not, the emphasis our society puts on the appreciation of our natural landscapes remains strong (National Park Service). Furthermore, a study by the University of Exeter revealed that spending 120 minutes in nature is associated with positive well-being (White et al.). For something that plays such a significant role in our everyday lives, it is concerning that relatively little attention is directed towards the conservation of our environment.

On top of the environment’s mindfulness effects, humans hold a moral responsibility to maintain the integrity of our planet’s environment. Consider, for example, a citizen’s allegiance to their home country. The citizen do not innately owe their home country anything—they could have been born in any arbitrary country and lived their life. But still, there is a sentimental attachment to their home country. The simple fact that their home country provided the initial foundations for the life they are able to live is typically a good enough reason to develop some level of patriotism. So why isn’t this exact mindset extended to our planet as a whole? Sure, one can argue that the most inconsequential species of bacteria has no bearing on our lives, but still, it serves a role in this complexity we call life. To be able to live at all is already the most fundamental and distinguished privilege a human can have, and the opportunity to live can only be attributed to the existence of our planet and its environment. Humans contribute to the balance that allows this life to flourish just as much as bacteria do, and as a result, we must hold ourselves accountable for the homeostasis of our planet.

Much like the ticking of the clock hanging behind my monitor, the future of climate change is often overshadowed by conventionally “important” issues. Yet just as the clock ticks away, our time with the treasured natural landscape will continue to deplete. By taking a step back and looking at our lives in the scope of the universe, we can begin to realize that there are more important objectives in life than maximizing profits and developing new technologies. One of the greatest gifts that humans have been bestowed upon is the simple ability to experience life, but as we take the natural marvels that populate our planet for granted, we surrender a defining trait of our existence. As Robin Williams famously said in Dead Poets Society, “medicine, law, business, engineering — these are noble pursuits and necessary to sustain life. But poetry, beauty, romance, love — these are what we stay alive for.” And what better source of beauty and love than the natural world around us?

Works Cited

Nadeem, Reem, and Reem Nadeem. “2. Top Problems Facing the U.S.” Pew Research Center, 18 July 2024, www.pewresearch.org/politics/2024/05/23/top-problems-facing-the-u-s.

Sheather, Julian, et al. “Ethics, climate change and health – a landscape review.” National Library of Medicine, 14 Aug. 2023, pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10483174.

Visitation Numbers (U.S. National Park Service). www.nps.gov/aboutus/visitation-numbers.htm.

White, Mathew P., et al. “Spending at Least 120 Minutes a Week in Nature Is Associated With Good Health and Wellbeing.” Scientific Reports, vol. 9, no. 1, June 2019, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-44097-3.

The views and opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect nor represent the Earth Chronicles and its editorial board.