Recently, I saw a photograph of a young woman with an elaborate display of red jewelry glowing on her chest. And only moments after reading the caption, I was surprised to discover the very jewels on her neck were actually made of Red Coral.

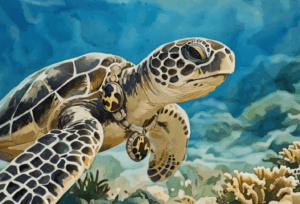

When most people think of coral, they think of thriving structures in movies such as Nemo or perhaps the Little Mermaid. They are the epitome of the classic humble abode to fish, marine life, and ocean critters. Their vibrancy sways in the sunlit waters as symbols of the beauties of the ocean. But what is exactly coral?

Coral are animals. Though they appear as colorful plants, corals are colonies of individual organisms called coral polyps. Polyps are invertebrates with a body, a mouth, and stinging tentacles. They use the seawater’s calcium carbonate to build their skeletal structure. The color you associate with coral comes from the polyp’s symbiotic relationship with zooxanthellae (an alage), using photosynthesis for food.

So if corals are animals, it got me wondering: What was the difference between the woman with the red coral necklace and someone else wearing the skin of an animal?

There are over 6,000 species of coral that can be found in shallow waters as well as the seafloor (National Geographic Society). According to the EPA, 25% of marine life depends on coral reefs in many forms (Environmental Protection Agency). Corals are most well known for providing around a million species a habitat and nursing grounds. But they also provide economic, cultural, and ecological benefits for humans as well. Many people in coastal areas depend on the food provided by coral reef ecosystems, such as fish. Economic benefits include the booming touristic and recreational activities and new forms of medicine. In addition, coral reefs act as a barrier to storms, floods, and erosion (Environmental Protection Agency). Ultimately, coral reefs provide humans with countless benefits, giving back to humans endlessly.

This brings me back to the Red Coral or Corallium Rubrum. Prized for their beautiful bloody red, people have been using Red Coral for a number of different uses as far back as the fifth-generation BC. For example, Red Coral has been used to “ward off danger, protect from the evil eye, decorate their battle spears, bring financial prosperity and cure infertility” (Barrat). Still, the red coral is valued as a gemstone associated with the god of warfare Mars; people believe there are many benefits to wearing this type of coral.

Unfortunately, the intensity of the harvesting of coral has driven this species to endangerment. Humans have been removing or destroying Red Coral, a slow-growing organism, faster than their rate of reproduction.

However, harvesting is not the only threat that Red Coral faces. Unsustainable fishing practices lead to habitat destruction on a large scale. The anchor lines, gill nets, and ropes can lead to “tissue abrasion” or colony detachment (Bavestrello et al. 1997). Another culprit of coral mortality is trawling, a fishing method that involves dragging a fishing net through the water to catch fish in large quantities. This method devastates the seafloor, swallowing or crushing nearly everything in its path. Human recreational activities such as diving have also disturbed the Red Coral’s ecosystems. Areas of high diving activity are correlated with increased partial mortality rates of red coral. For example, one study compared the Medes Islands Marine Reserve (unrestricted recreational diving) with Banyuls, Carryle-Rouet, and Scandola (both fishing and diving activities prohibited). The results revealed that the Medes Islands Marine Reserves had smaller red coral colonies than the three other areas. The study concluded that diving activities could lead to abrasion, increasing coral mortality (Linares et al. 2012). And lastly, but most importantly, ocean warming and climate change have led to mass mortality events. Areas experiencing increased water temperatures also saw a rise in mortality rates and broader ranges of affected coral populations. In one study, scientists gathered data on water temperature, depth, and gorgonian mortality in the summer of 1999 at the Ligurian Sea. They noted that the red coral “quickly lost their coenenchyme and filamentous algae and campanulariid hydroids rapidly colonized the naked skeletal axis” (Cerrano et al. 2000; Pérez et al. 2000; Garrabou et al. 2001,2009; Benssousan et al. 2010; Crisci et al. 2011).

So what has been done to conserve the Red Coral?

Attempts to protect coral and lower coral fishery were made in the mid-1980s; later, in 2007, the United States and the European Union proposed to protect red coral through CITES and trade restrictions. This attempt was struck down by industrial lobbyists (Barrat).

Some acted on the decline of red coral with restoration techniques. Coral transplant projects transplanted not only fragments but sometimes branches and the whole coral. Coral gardening techniques were used by the EU-funded CORGARD project as well. Red coral larvae were raised in aquarium tanks and transplanted in areas with depleted coral populations. Other conservation actions promoted by the FAO-GFCM called for the banning of highly destructive unsustainable fishing systems (“ingegno” trawling and tangling nets”) and prohibition of fishing in a certain 50 m depth range. However, many countries have yet to implement these regulations as they were not legally binding but rather a “recommendation” (IUCN).

However, according to the IUCN red list, the Red Coral species are still declining and endangered, proving that we must do more to conserve coral. As Alison Barrat puts it, “the larger the coral, the more it can reproduce. Without any large corals left on the reef, recovery of the previously fished area is unlikely” (Barrat). Immediate action is necessary to conserve the coral reefs and the entire ecosystem and marine life that depends on them.

So what can we do?

There are countless changes we as humans can make daily. For example, reducing our carbon footprint will help stop climate change and warming oceans, resulting in coral bleaching. One significant habitual difference you can make is to reduce water use by using water-saving appliances, reducing shower time, planting drought-resistant or native crops, installing rain catchers, and using drip irrigation. Conserving water can also lead to less runoff and wastewater. Another is reducing waste production by recycling correctly or, even better, reducing your consumption in the first place. Next time you go to a coffee shop, bring your own tumbler instead of using their disposable cups. You can also make sustainable food choices; for example, choose sustainably fished seafood, reduce your meat intake, or buy from locally grown farms. And lastly, you can also reduce carbon emissions by driving less, purchasing emission-free vehicles, carpooling, choosing mass transit, biking, or walking.

Other solutions include volunteering at events such as a local beach or reef clean-ups. Or instead, your clean-up days can be completely self-organized; you can go “plogging” (picking up trash while jogging). Another solution is passing regulations that will protect our coral reefs. And you are fully capable of doing so. Reach out to your local government to talk about your city’s energy or waste production. Or you can even research more on the current Mediterranean policies for coral reefs and reach out to them as well. In addition, next time you visit a coral reef, don’t touch them, dive too close to them, and certainly do not break or gift them. Coral reefs, in essence, are a gift that provides us numerous ecological and economic benefits, and that is enough.

The most important solution is to stay informed. Education is key to being conscious of our impact on not only red coral but our planet as a whole. In order to create massive change, we need to change the culture of our communities; we need to change the misconceptions about our planet and fully mobilize towards sustainability. And to do so, we all need to educate ourselves and spread awareness on topics such as our impact on the endangered red coral.

While it is important to respect the different cultures whose beliefs depend on the harvesting of red coral, it is equally as crucial to regulate and restrict illegal or overly-intense activities. Everybody can reduce their carbon footprint to reduce coral bleaching and mass mortality events. At the same time, the government can pass legally binding regulations to enforce the banning of illegal and destructive practices such as trawling.

It’s important to remember that nature is able to live in harmony because of the principles of sustainability and the ability of Earth’s life cycles to adjust and stay resilient. But when human activity destroys habitats or interrupts these cycles faster than recovery, this can lead to severe consequences. Red corals are animals, not the blood jewels of the ocean.

Works Cited

Barrat, A. (2015, January 22). Red coral: What’s the future? Living Oceans Foundation.

Bavestrello, G., Cerrano, C., Zanzi, D. and Cattaneo-Vietti, R. 1997. Damage by fishing

activities in the Gorgonian coral Paramuricea clavata in the Ligurian Sea. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems 7: 253-262 pp.

Cerrano, C., Bavestrello, G., Bianchi, C.N., Cattaneo-Vietti, R., Bava, S., Morganti, C., Morri,

C., Picco, P., Sara, G.., Schiaparelli, S., Siccardi, A. and Sponga, F. 2000. A catastrophic mass-mortality episode of gorgonians and other organisms in the Ligurian Sea (northwestern Mediterranean), summer 1999. Ecology Letters 3: 284–293 pp.

Coral. National Geographic Society. (n.d.). Retrieved May 31, 2022, from

https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/coral .

Environmental Protection Agency. (n.d.). Basic Information about Coral Reefs. EPA. Retrieved

May 31, 2022, from https://www.epa.gov/coral-reefs/basic-information-about-coral-reefs#:~:text=Coral%20reefs%20are%20among%20the,point%20in%20their%20life%20cycle

Guardian News and Media. (2010, February 18). Deep-sea trawling is destroying coral reefs and

pristine marine habitats. The Guardian. Retrieved May 31, 2022, from https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2010/feb/18/deep-sea-trawling-coral-reefs

Linares, C, Garrabou, J, Hereu, B, Díaz, D, Marschal, C, Sala, E, Zabala, M. 2012.

Beyond fishes: assessing the effectiveness of marine reserves on overexploited long-lived sessile invertebrates. . Conservation Biology 26: 88-96.

Lionello, P. (ed). 2012. The Climate of the Mediterranean Region From the past to the

future. Elsevier, Oxford.

(Oceana), S. G., Barcelona), C. L. (U. de, Garrabou, J., Oscar Ocaña (Fundación Museo del

Mar), Carlo Cerrano (Università Politecnica delle Marche), Bologna), S. G. (U. of, Ricardo Cattaneo-Vietti (University of Genoa), & Genoa), G. B. (U. of. (2014, October 1). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved May 31, 2022, from https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/50013405/110609252

The views and opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect nor represent the Earth Chronicles and its editorial board.