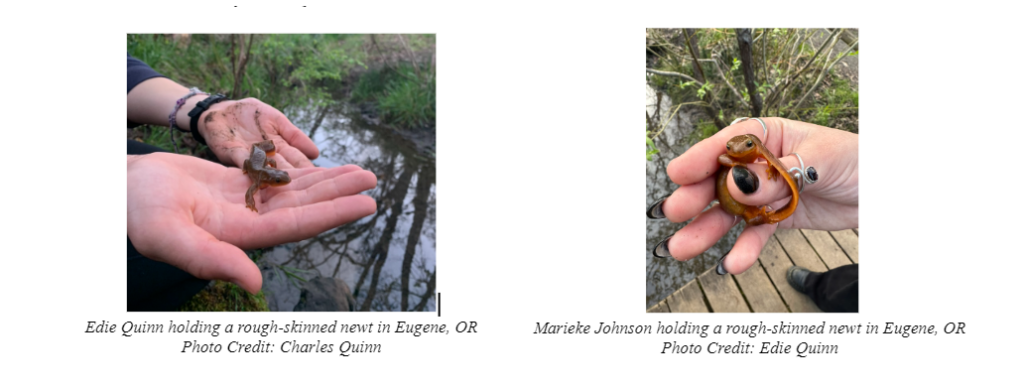

Ever since I was a little girl, I remember splashing into the cold, clear water of the creeks surrounding my house and preschool in search of rough-skinned newts. With their cute buggy eyes and vibrant orange bellies, they were a creature my little hands couldn’t wait to catch. Always with care and admiration for the newts, I would scoop them up from the soft muddy bottom and look into their eyes. In those moments we understood from each other—newt and child—that although small and unassuming, we deserved our place in this big world.

“Don’t litter! Protect the watersheds! Keep street drainage away from our streams!” We are constantly bombarded with all of these commands to look after our natural world, but it’s important to remember the passion that drives us to do so. For me, that passion is ensuring the health of ecosystems in which amphibians thrive so that I can continue to see one of my favorites, the rough-skinned newt. Found along the West Coast of North America from southeastern Alaska to the California Bay Area, they are a prominent pacific northwest amphibian representative (Powers). For most of the year they are found on lush forest floors amid the moss, logs and ferns, or grasslands near lakes, ponds, or creeks (Powers). They are usually around 3.5 to 8 inches in length, so keep your eyes peeled as you take your hikes if you want to spot them(Rough-skinned Newt)! When it comes time to mate around December, they make their way back to still or slow moving bodies of water like the ones they hatched in, and remain primarily aquatic until the end of their mating season, often in April, but in some areas lasting until June (Rough-skinned Newt).

Rough-skinned newts are truly extraordinary creatures with a brown back and are distinctly identifiable by their brightly colored orange belly which serves as a warning sign to potential predators. As many animals do, the bright orange signifies their toxicity. When threatened, the newts will assume a defensive posture called “unken reflex” in which they will rear their head and coil up their tail to display their bright orange bellies (Rough-skinned Newt). They will then release a powerful neurological poison, tetrodotoxin, in the form of a milky-looking fluid which results in the paralyzation and asphyxiation of the predator if consumed (“Tetrodotoxin: Biotoxin”). These symptoms apply to humans as well, so make sure to wash your hands after handling them, even if you do not see the fluid released. The eggs contain this toxin as well so as to be protected in their most vulnerable stage. Miraculously, due to coevolution, the common garter snakes present in areas with rough-skinned newts have assumed a biochemical defense against the toxin, making them the sole predator able to survive a meal of rough-skinned newts (Powers).

Rough-skinned newts are just one of many fascinating creatures that make our world worth looking after. I encourage everyone, including myself, to reconnect with the reason we choose to educate ourselves about our environment and harness that passion into actively protecting it. Whether it’s taking that quicker shower or that extra moment to sort your recycling, every step counts. Let’s take those extra moments and look after the little guys!

[Note: in most of the San Francisco Bay Area, you are more likely to see the California newt, a close relative of the Rough-skinned. See https://californiaherps.com/salamanders/pages/t.granulosa.html for how to tell them apart.]

The views and opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect nor represent the Earth Chronicles and its editorial board.